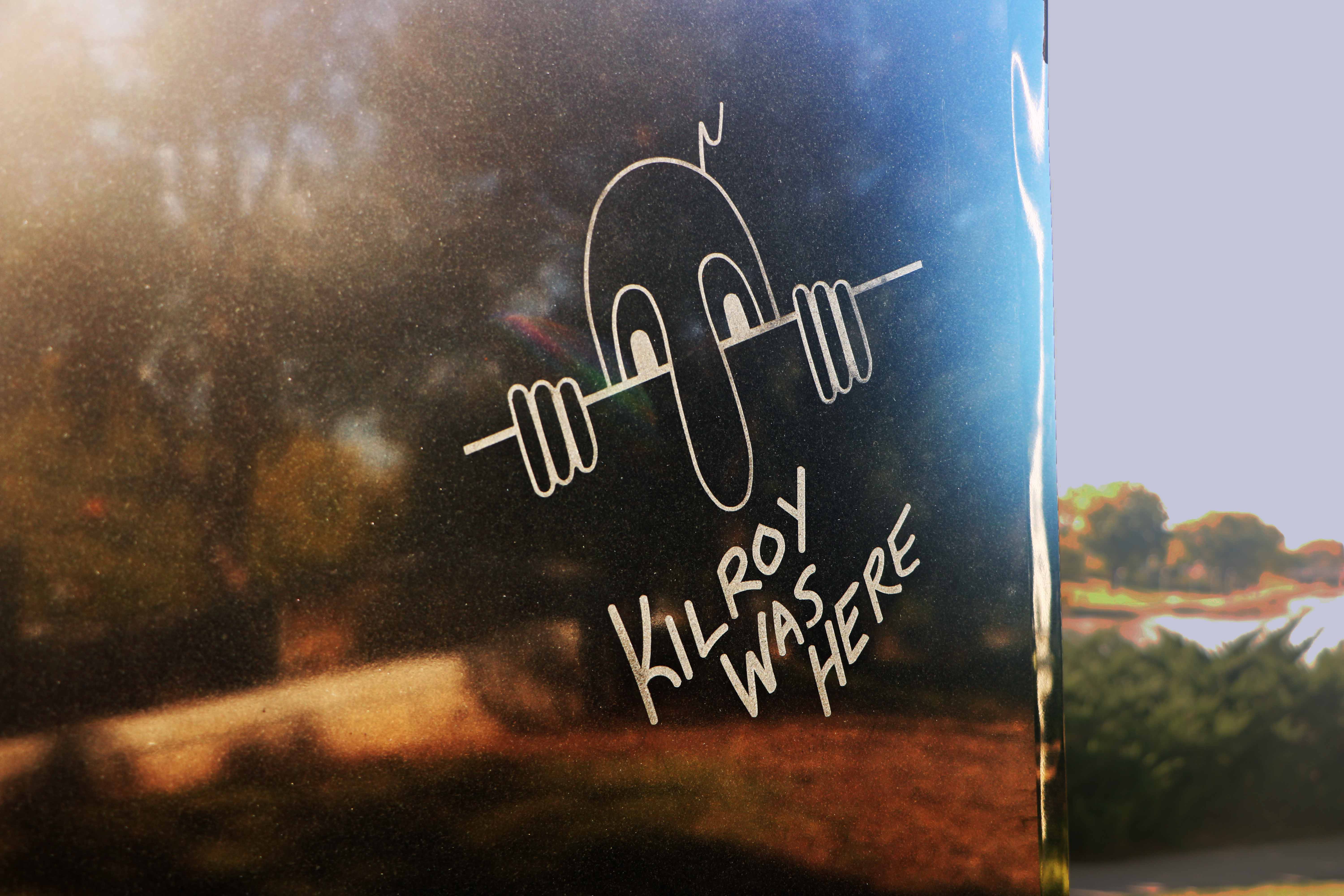

The Oxford English Dictionary says simply that Kilroy was “The name of a mythical person”. One theory identifies James J. Kilroy (1902–1962), an American shipyard inspector, as the man behind the signature. The New York Times indicated J.J. Kilroy as the origin in 1946, based on the results of a contest conducted by the Amalgamated Transit Union to establish the origin of the phenomenon. The article noted that Kilroy had marked the ships themselves as they were being built—so, at a later date, the phrase would be found chalked in places that no graffiti-artist could have reached (inside sealed hull spaces, for example), which then fed the mythical significance of the phrase—after all, if Kilroy could leave his mark there, who knew where else he could go? Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable notes this as a possible origin, but suggests that “the phrase grew by accident.”

During World War II he worked at the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts, where he claimed to have used the phrase to mark rivets he had checked. The builders, whose rivets J.J. Kilroy was counting, were paid depending on the number of rivets they put in. A riveter would make a chalk mark at the end of his or her shift to show where he had left off and the next riveter had started. Unscrupulous riveters discovered that, if they started work before the inspector arrived, they could receive extra pay by erasing the previous worker’s chalk mark and chalking a mark farther back on the same seam, giving themselves credit for some of the previous riveter’s work. J.J. Kilroy stopped this practice by writing “Kilroy was here” at the site of each chalk mark. At the time, ships were being sent out before they had been painted, so when sealed areas were opened for maintenance, soldiers found an unexplained name scrawled. Thousands of servicemen may have potentially seen his slogan on the outgoing ships and Kilroy’s apparent omnipresence and inscrutability sparked a legend. The slogan began to be regarded as proof that a ship had been checked well, and as a kind of protective talisman. Afterwards, servicemen began placing the slogan on different places and especially in newly captured areas or landings, and the phrase took on connotations of the presence or protection of the US armed forces.

The Lowell Sun reported in November 1945, with the headline “How Kilroy Got There”, that a 21-year old soldier from Everett, Sgt. Francis J. Kilroy, Jr., wrote “Kilroy will be here next week” on a barracks bulletin board at a Boca Raton airbase while ill with flu, and the phrase was picked up by other airmen and quickly spread abroad. The Associated Press similarly reported at the same time that according to Sgt. Kilroy, when he was hospitalized early in World War II a friend of his, Sgt. James Maloney, wrote the phrase on a bulletin board. Maloney continued to write the shortened phrase when he was shipped out a month later, and other airmen soon picked up the phrase. Francis Kilroy himself only wrote the phrase a couple of times.

F D Sharp

Posted at 00:21h, 13 AprilWilliam “Bill” “Tuck” Tucker: As a P-38 pilot, I was station in the China/Burma/India area. I had heard about the B-29 but had yet to see one. When flying a practice mission one day, I heard a tremendous noise. Looking around, here came a B-29. What a marvelous bird! I had to keep flying just to observe that monster!

Being a “daredevil”-type of guy, I enjoyed playing with the P-38’s abilities. Meeting a lovely English nurse stationed at our base, she wanted to fly in the P-38. I made arrangements, sort of, for her to go up in the plane with me. While flying, I decided to see if she could handle a roll in that plane. We did the roll, and after catching her breath, she declared “Do it again, Tuck! Do it again!”

Francene Davis Sharp

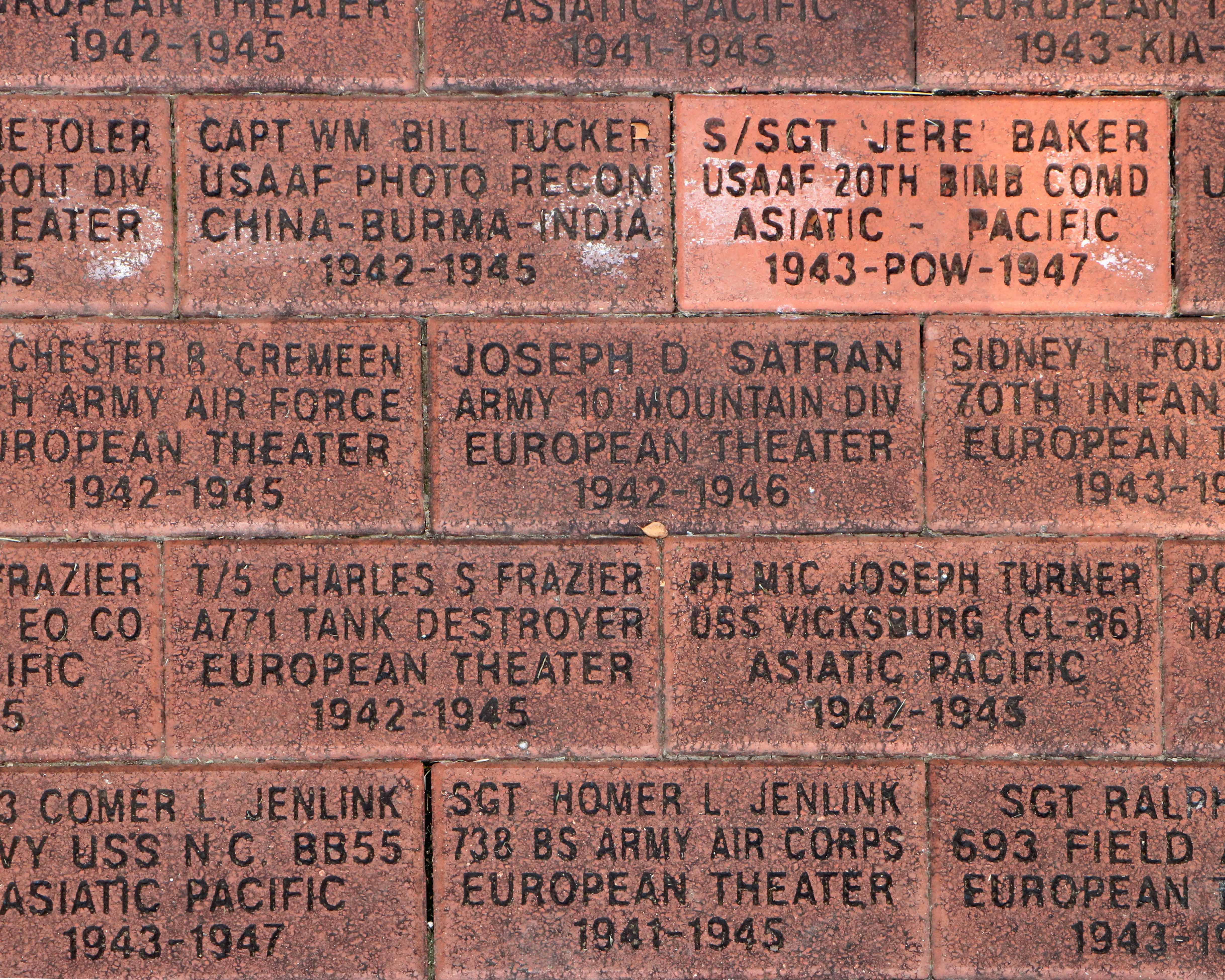

Posted at 20:15h, 13 April“Jere” Baker, (he hated his real name, Jeremiah), was part of the 58th Bomb Group, “The Hellbirds”. He has the “honor” of being the last B-29 shot down during WW II. They landed in water, hoping that “friendlies” would be able to rescue them, but it was not to be. Everyone on that plan survived except the rear gunner whom they could never find. Taken captive by the Japanese, they were held in a cave, secured in small wooden boxes. They were allowed out 1 hour every 24 hours, sometimes fed a few grains of hard rice, and found that bugs could be very “delicious”. Photos document the under 100 lbs which most were at the end of the month — when the war was over. Afraid of being killed, those who had captured the plane load of soldiers ran off, leaving them still in their crates. One soldier was able to finally escape and let the others out. They waved down an American plane and were rescued.

Doug Rupe

Posted at 20:17h, 13 AprilKenneth Rupe departed New York harbor in August 1943, serving with the 300th General Hospital group, arriving in Bizertte, North Africa, and then onto Vomero, Italy outside of Naples. He served there for the duration of the war, not returning home until December, 1945.

Francene Davis Sharp

Posted at 20:17h, 13 AprilEugene “Gene” Toler, Infantry, France. He was my neighbor when we moved into the neighborhood, I was four. We remained friends thru the day of his death. I had the job to care for him in his late years and he told me this story of his time in the winter, in a foxhole:

It was cold! They had eaten all of their rations and one soldier had some coffee left. They scraped the paraffin off the cardboard boxes, (which had contained their rations), and built a fire for coffee — but they needed water.

Gene volunteered to crawl out and bring back some snow. After a few trips, they had enough snow for the coffee.

Gene said that it was the best coffee they ever drank — even if it did taste a little like pine!

Jack E Niblack

Posted at 20:18h, 13 AprilMy father, Jack A. Niblack, was a proud member of the 101st airborne division, The Screaming Eagles, during WWII. He jumped into France as part of the D-Day invasion, was one of the “Battlin Bastards of Bastogne,” and jumped into Holland as well. He won a purple heart for an injury he sustained. My father was never able to tell me any details about his service. He would simply say that he “had seen things that no human being should ever see.” He was a devout patriot and instilled in me a pride of country and of service to others. He was and is a real hero to me.

Ted Ayres on behalf of Bob Rogers

Posted at 20:18h, 13 April“We were alone on the ocean, no convoy, just a big boat full of GI’s. ‘Would a U-boat see us? I guess not.’ We arrived in Glasgow, Scotland in early March [1944] and got on a British Troop Train traveling across Scotland and into Wales. Abergevenny, Wales, a peaceful town, with a name that was hard to pronounce. We were expected; they gave us mattress pads and showed us where the straw was, our bunks were small and we were back to two meals a day. The first night we were there we were greeted by Bed-Check-Charley, a German Recon Plane that the Brits didn’t bother to fire at. I guess they wanted him to go back and tell them at German head quarters that I had arrived and to give up. Ha! Ha!”

The above is an excerpt from a manuscript written by Bob called “My Best and Worst of Times – Wonderful” and described as “In My Own Words As I Recalled it Many Years Later.” Thanks for your service Bob!

Ted D Ayres

Posted at 20:19h, 13 AprilI am pleased that my Father (Dean A. Ayres) and two Uncles (Glenn E. Murphy and Von Gentry) are memorialized at the World War II Memorial at Veterans Memorial Park. My Dad never spoke much about his service and all I really knew was that he was awarded the Purple Heart and that a piece of shrapnel went into his leg when his truck went over a land mine, a piece of shrapnel that was in his leg until the day he died. However, upon looking at my Dad’s Discharge Papers, I learned a great deal. I learned that he served for 24 months in the European Theatre and that he was involved in the following battles or campaigns: Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes and Central Europe. I learned that he drove a “… 2 1/2 ton truck hauling personnel and equipment to front lines … [and] Drove over very poor roads often under enemy fire.” In addition to the Purple Heart, Dad was awarded 5 Bronze Stars for his involvement in the above-referenced campaigns and the Good Conduct Medal. Dad, you are a honor to your family, including me and my sister, Becky, and your grandchildren and great-grandchildren. We will never forget you!

Molly McMillan

Posted at 20:20h, 13 AprilMy dad, Harold Odiorne, served in the Navy in Panama and then in the Pacific. My mom made war supplies in a factory in Iowa. Dad was lucky. On a transport ship to Panama, they were fired upon with two torpedoes. Thanks to quick maneuvering, both of them missed. Another night in the Pacific, dad was on an LST at an island with several other ships. They had gotten word that Japanese planes were on their way. All the ships put up cloud cover, but the one on dad’s LST wouldn’t work. It was a clear night with a full moon. They were sitting ducks, dad said. Our pilots chased them off. Dad had lots of stories. I sure do miss him.

Tim Sutherland

Posted at 20:20h, 13 AprilJames R West was my wife’s uncle. He passed away in 1994. Jim was in the 103rd and the only thing he ever shared was he walked all the way to Berlin. Jim was a awesome man who I got to spend a lot of time with and grew much respect for. Jim was the typical Tennessee home grown person who went by the nick name “Hillbilly” . His favorite trademark was to extend his middle finger in respect as you arrived or departed. Accompanied by his laugh. Jim retired from Cessna around 1989. My wife and I purchased their home from him and Genene when he retired and we still live in it today. I miss having him around for card games and just good fun.